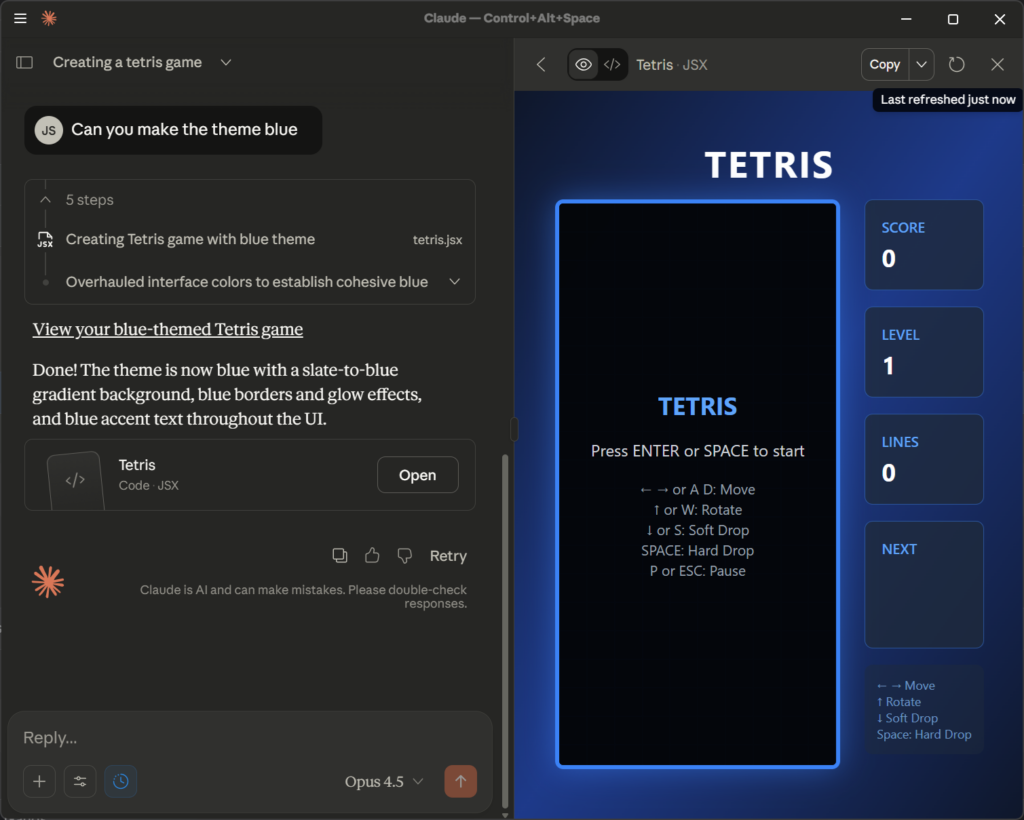

Safe AI Development Using Docker

One of the issues with using tools like Claude CLI or Gemini CLI is that you have to closely monitor each command they run. This can sometimes lead to mindlessly pressing “ok” or letting the AI run commands that later prove problematic. These CLI AI tools have full access to everything you have access to. If you can drop a database, they can drop a database. If you can delete a file, they can delete a file.

The problem is you either monitor every command or you run the risk of the AI damaging something.

There are several ways to “sandbox” AI from your environment. I use Docker as it accomplishes two tasks: it helps protect resources from inadvertent AI changes, and it helps set up a way to deploy services and web apps to production.

In this series of posts and videos, I will be reviewing how I use Docker for TypeScript and PHP development with AI tools like Claude CLI and Gemini CLI.

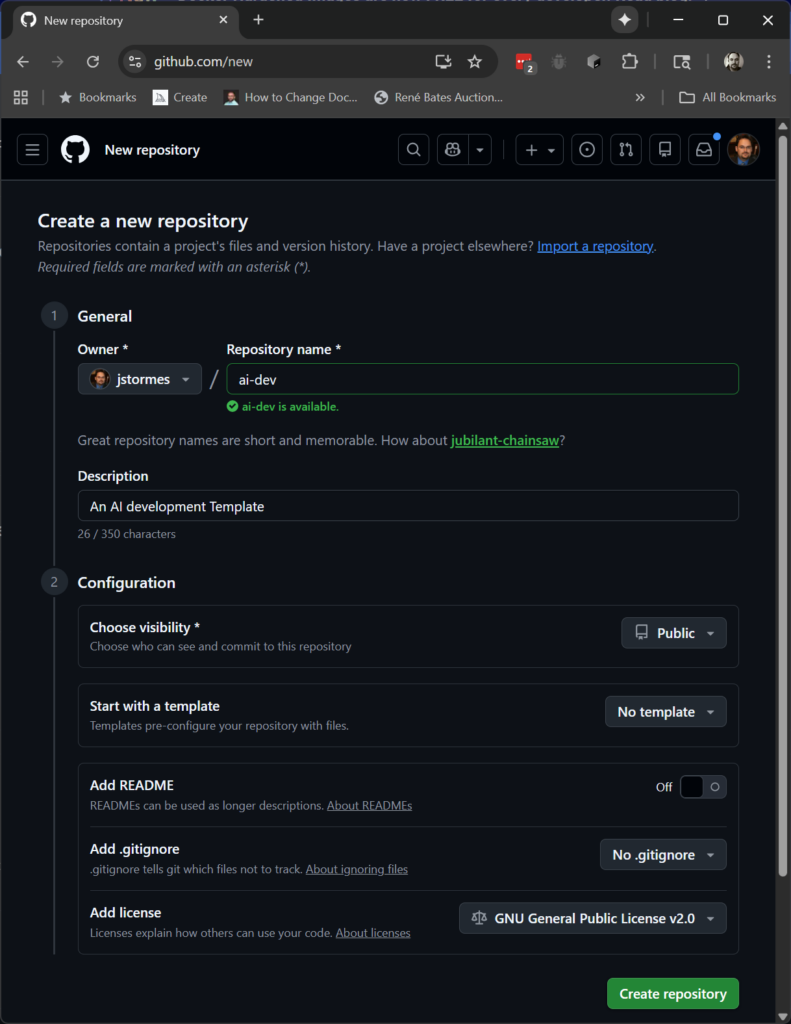

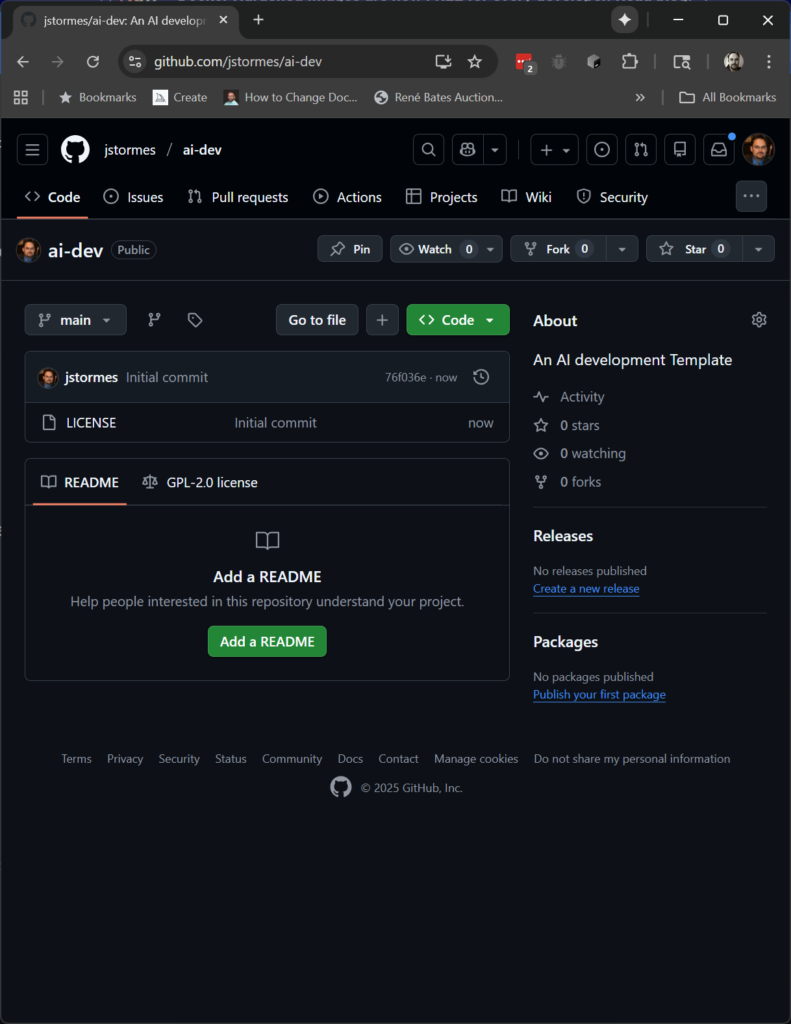

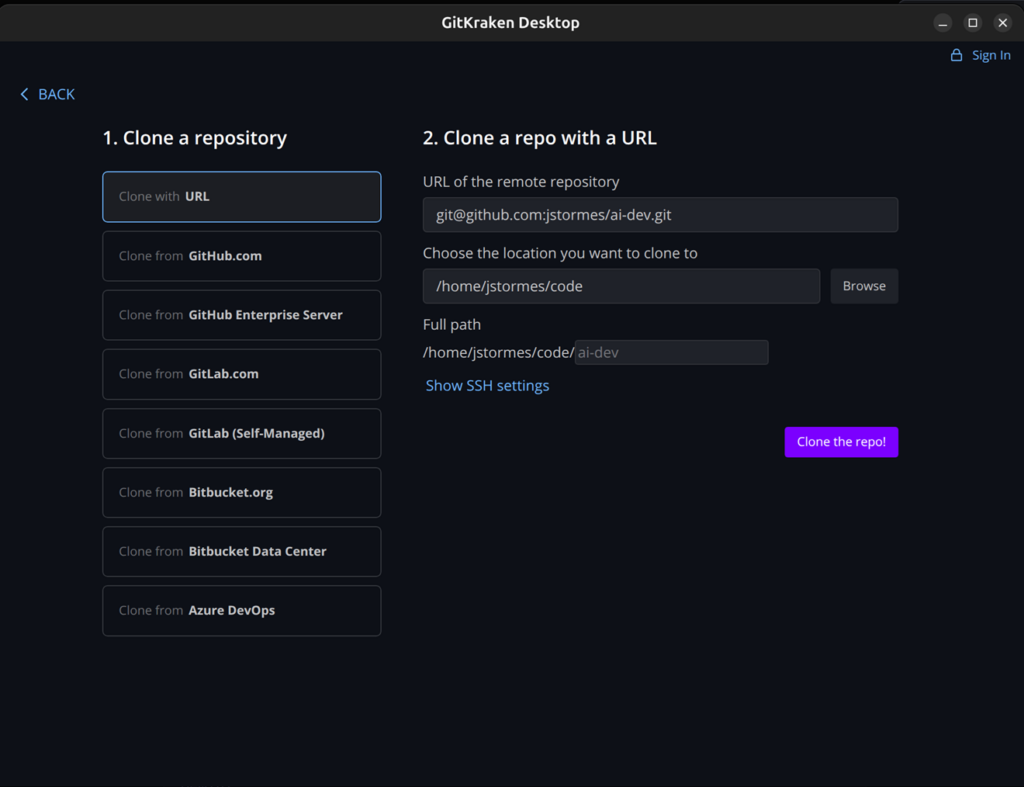

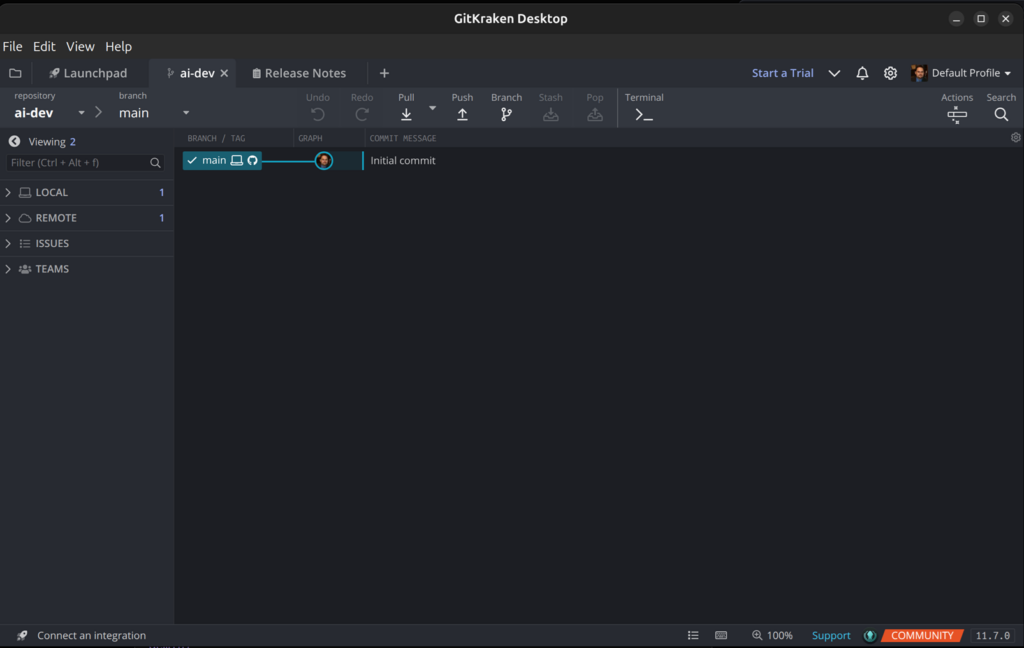

Creating a Git Project to Hold Our “Dev Environment as Code”

For this task we start where we always start as developers: with Git.

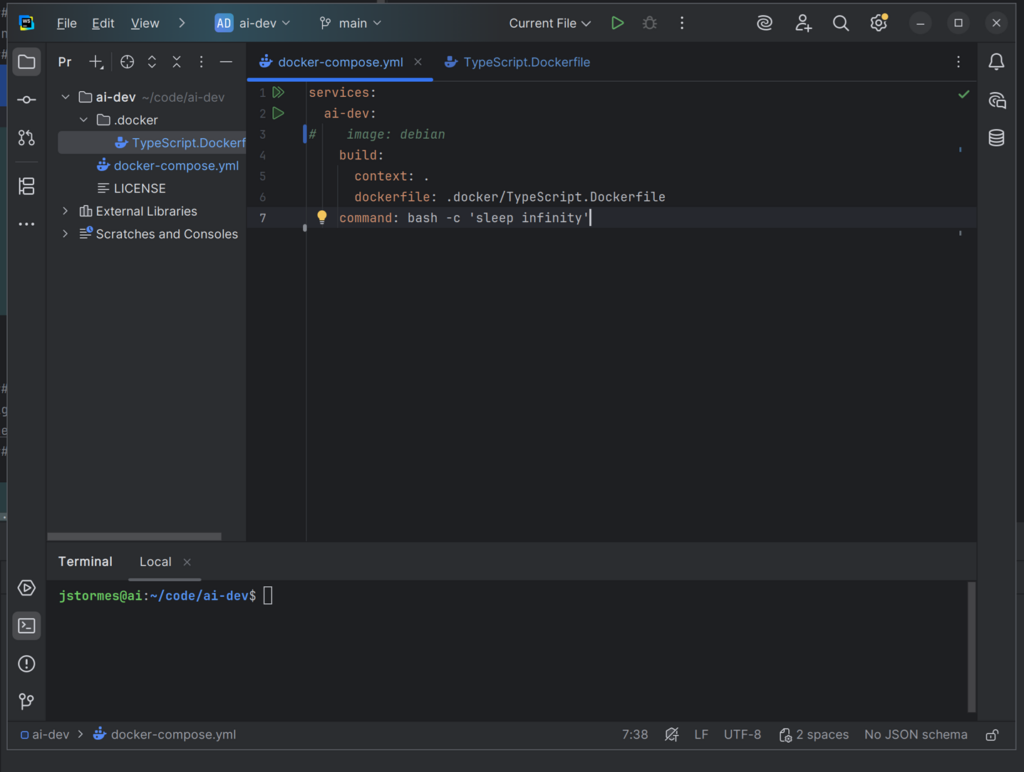

Creating the docker-compose.yml Config File

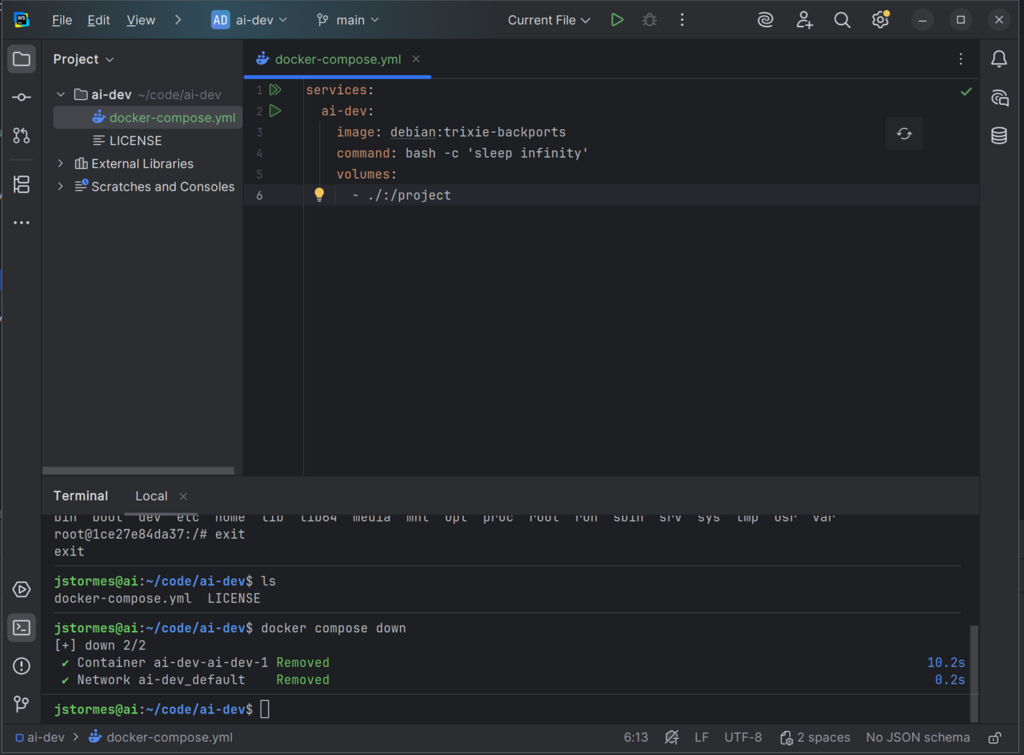

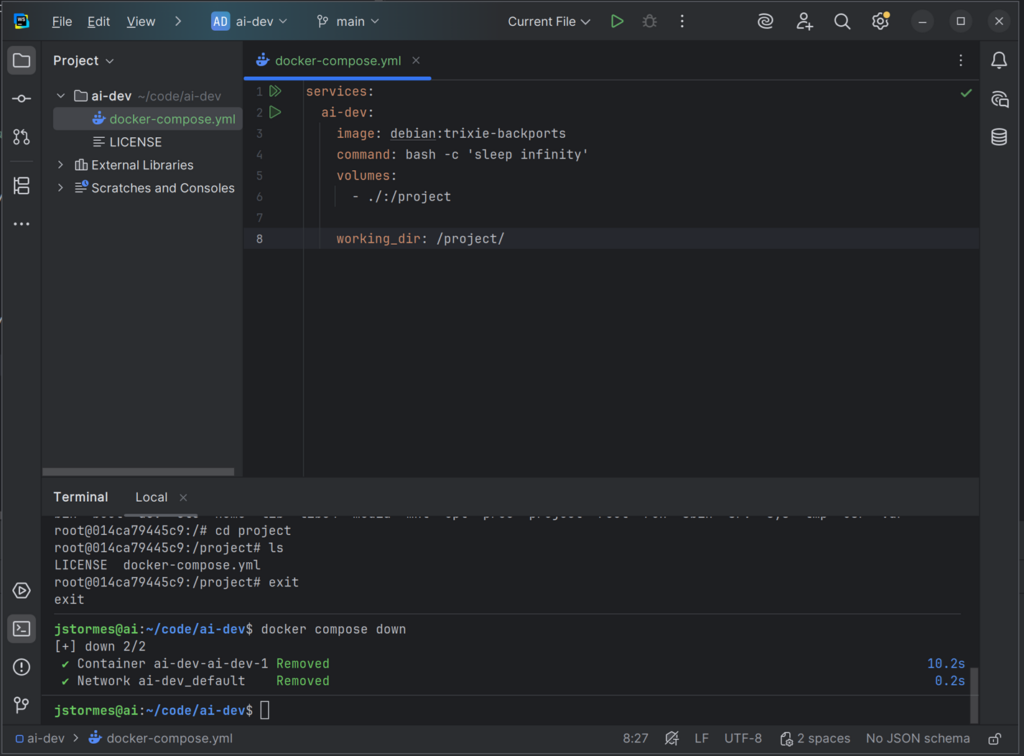

The next thing to do is create our docker-compose.yml. This is the file that configures Docker.

The first line needs to be services:. This is where we will start to list the services (aka servers) we want to run.

Below that will be the name we want to give our service. In this case we will name the first service ai-dev.

For now we will use a Docker image for our service. The next line needs to be image: debian. Below that add command: bash -c 'sleep infinity'.

Note that each line is indented one tab from the previous line.

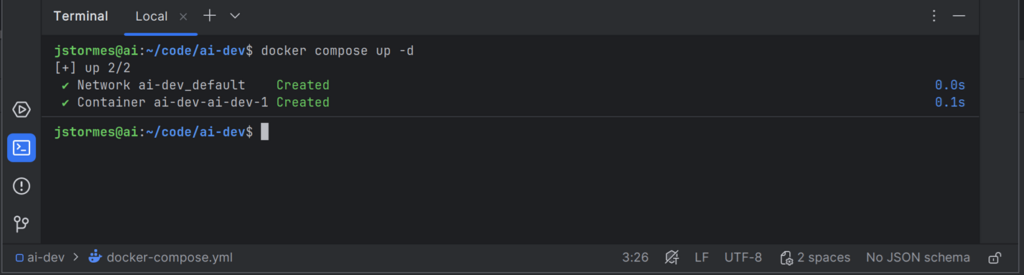

This is enough to test our first service. Make sure that file is saved, and from the command line in the same directory as the docker-compose.yml file, run:

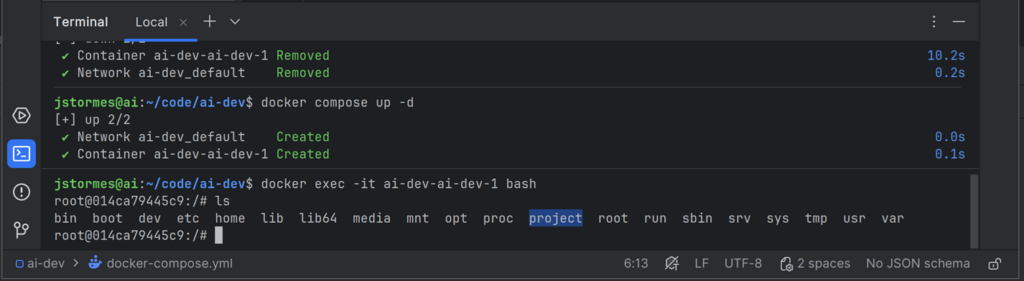

docker compose up -d

NOTE: You may see several additional lines as Docker downloads all the resources needed to build the service, but eventually you should see the command prompt again.

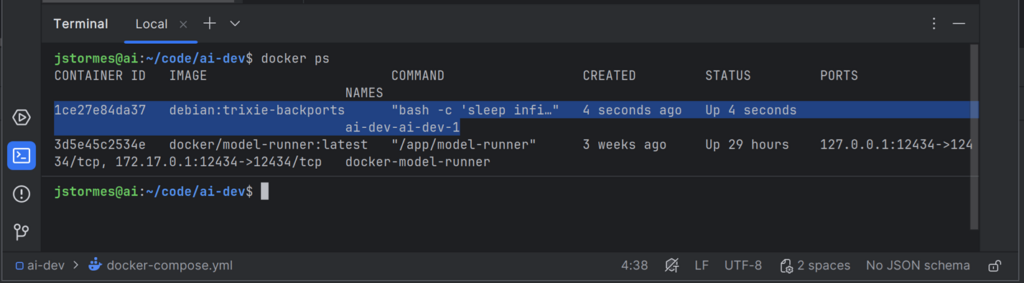

Run:

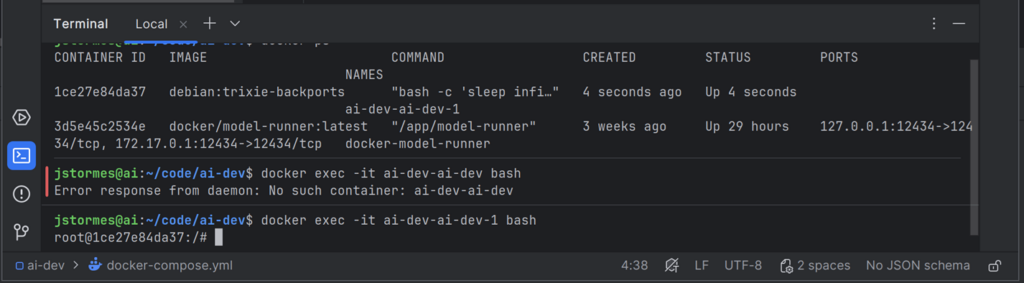

docker ps

Note the line highlighted in blue. This is our running container.

To get a command line into the container, run:

docker exec -it ai-dev-ai-dev-1 bash

This command will open a command line inside the running container.

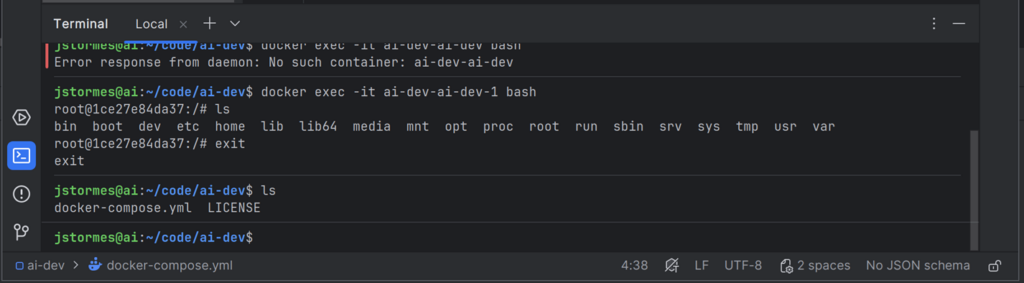

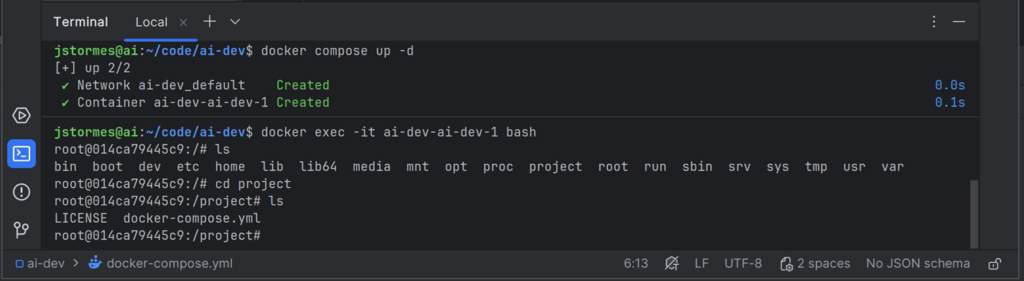

If we run ls inside the container, we can see the root files of the container. We can type exit to leave the container, and run ls again to see the files in our project.

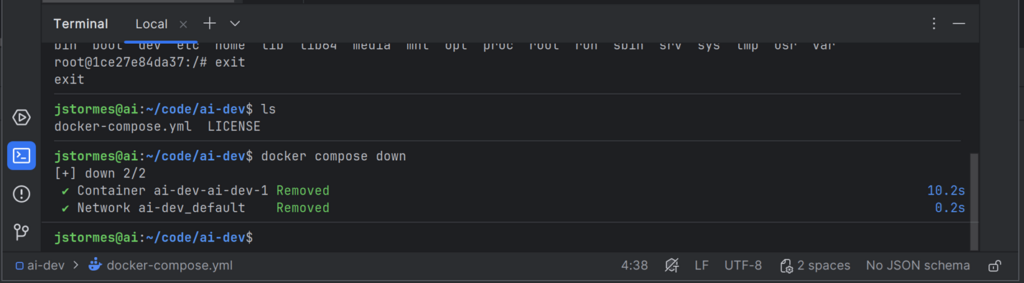

Running docker compose down from the directory with the docker-compose.yml file will shut down the container(s).

We now have two worlds that are separated from each other: the “inside the container” world and the “outside the container” world. We can use this to set up our safe AI development environment.

Mapping Directories into the Container

This container world is all well and good, but we need to get our “code” inside it.

To do that we can map a volume from outside the container to inside the container by adding the lines volumes: followed by the path we want to map: - ./:/project.

We can start our container again with docker compose up -d and go “inside” with docker exec -it ai-dev-ai-dev-1 bash.

If we run ls again we will see our project directory inside our container.

If we cd project we can then see our files from outside the container.

Let’s run exit again and docker compose down to leave and clean up our container(s).

We can set the default working directory to project by adding the line working_dir: /project/ to our docker-compose.yml.

We now can map files into our container.

Installing Claude Inside Our Container

Now we need to start customizing our container by installing Claude CLI in it.

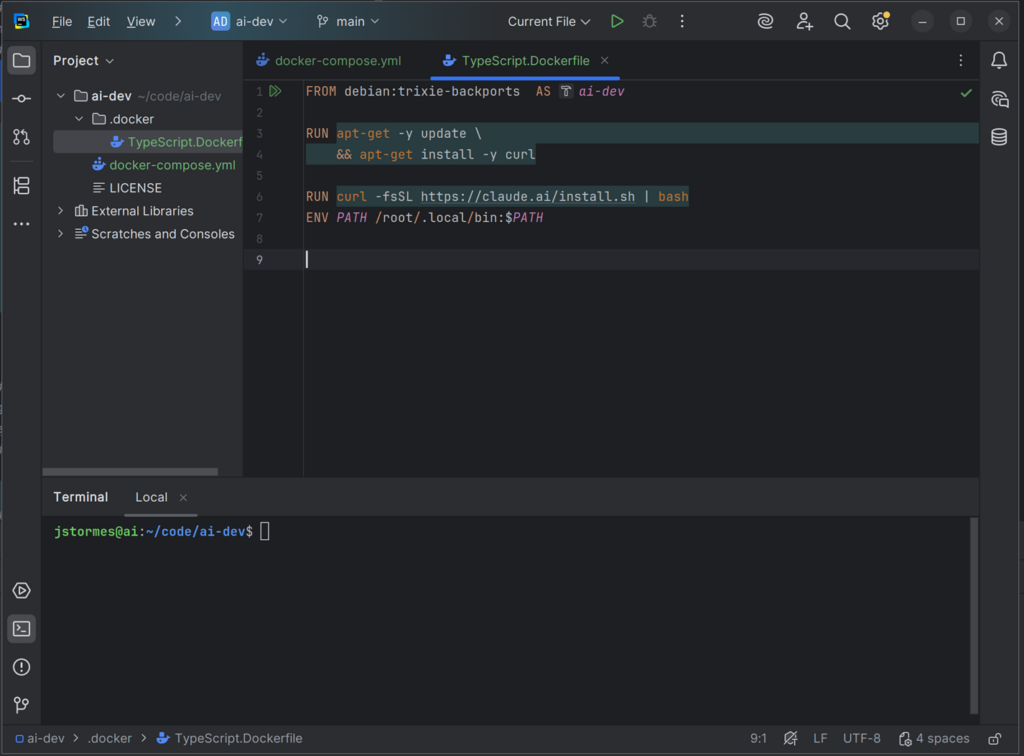

To do that we will start by adding a directory called .docker to our project. After that, create a file called TypeScript.Dockerfile inside it.

This file will be our custom setup for our ai-dev container.

In that file add the line FROM debian AS ai-dev. This tells Docker to use the same Debian-based image that we are using in the docker-compose.yml file.

Next we need to add curl so we can download Claude:

RUN apt-get -y update \

&& apt-get install -y curl

Then we can add Claude:

RUN curl -fsSL https://claude.ai/install.sh | bash

ENV PATH /root/.local/bin:$PATH

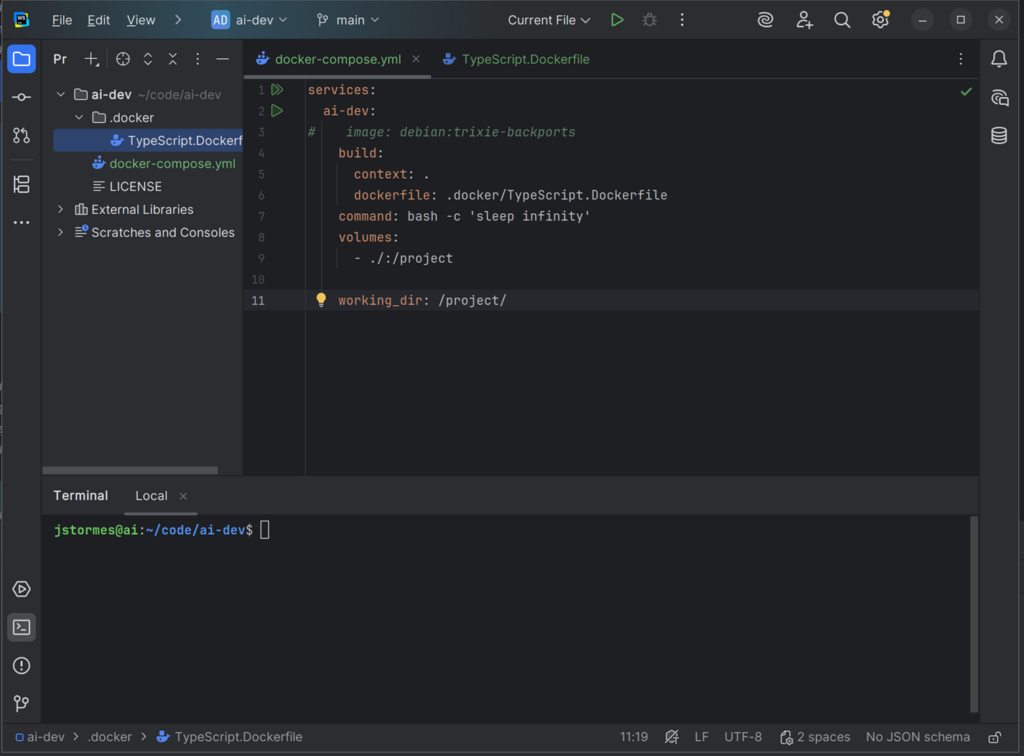

Finally we need to tell our docker-compose.yml to use our new file:

services:

ai-dev:

# image: debian:trixie-backports

build:

context: .

dockerfile: .docker/TypeScript.Dockerfile

command: bash -c 'sleep infinity'

volumes:

- ./:/project

working_dir: /project/

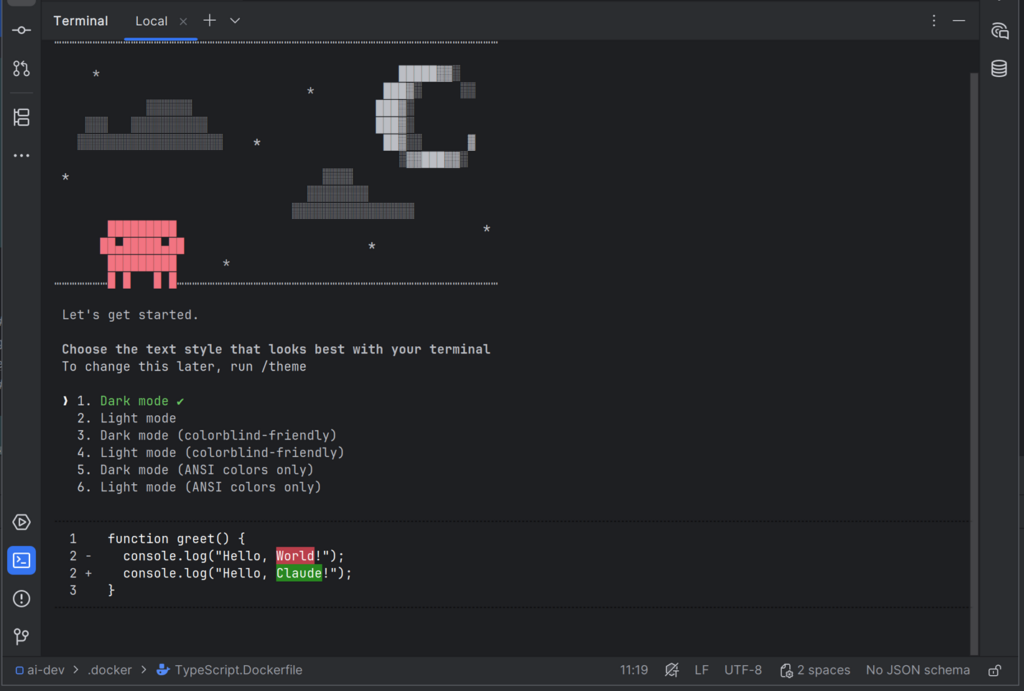

Now we run docker compose build to build our new image, followed by docker compose up -d and docker exec -it ai-dev-ai-dev-1 bash. We can now run claude inside our container.

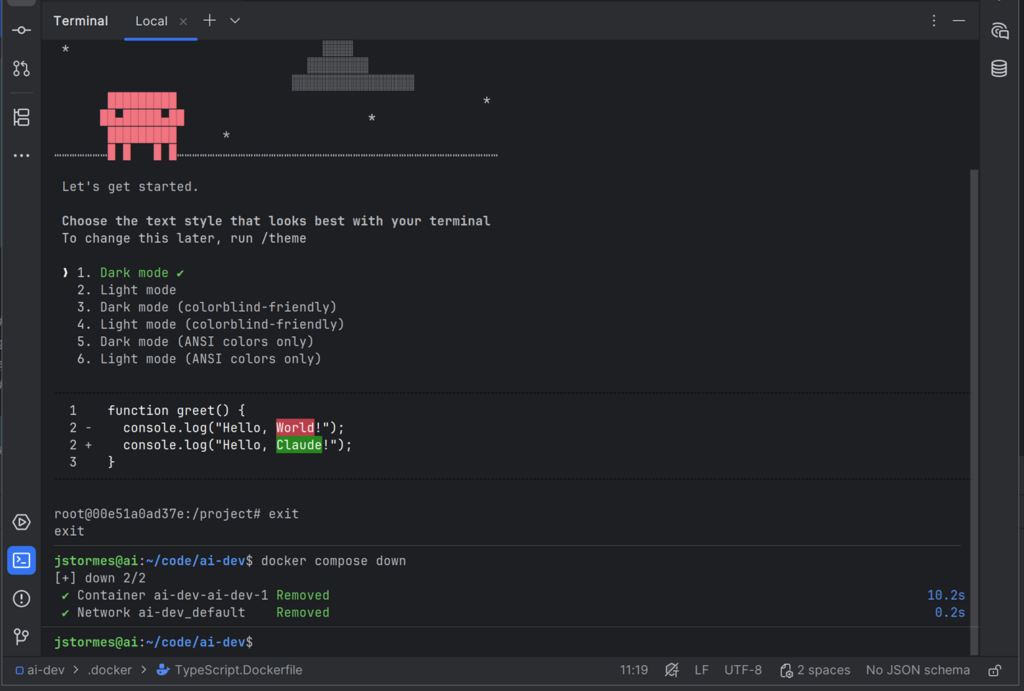

Press Ctrl+C to exit Claude, then type exit followed by docker compose down to clean up.

This is a super minimal Docker-protected AI development setup.

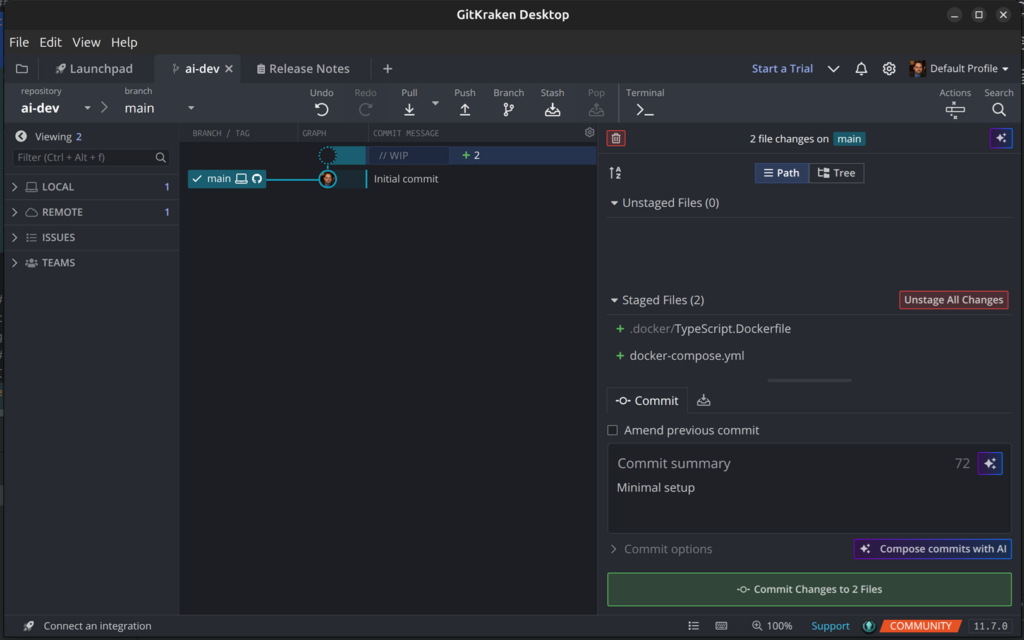

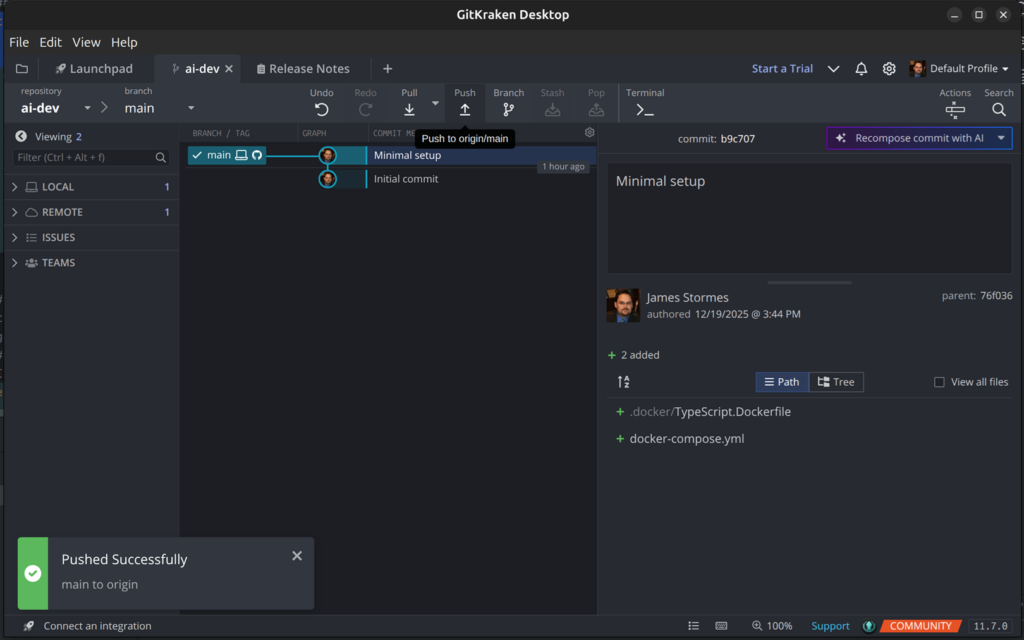

Finally we will commit and push.

In the next post we will make it more useful by passing our Claude login and adding tools for Claude to use.